Bhubaneswar:Battling low wages and rising bear attacks, these temporary educators serve students of semi-nomadic communities for six months every year.

Sadaf Shabir and Fahim Mattoo

Anantnag, Jammu and Kashmir: “My children study in Class IV and V. They are the first in our whole family to attend a school,” Mohammad Yousuf, a member of the Bakarwal community, beams with pride as he sees off his two children to their seasonal school at Chindermarg in Anantnag district of Kashmir.

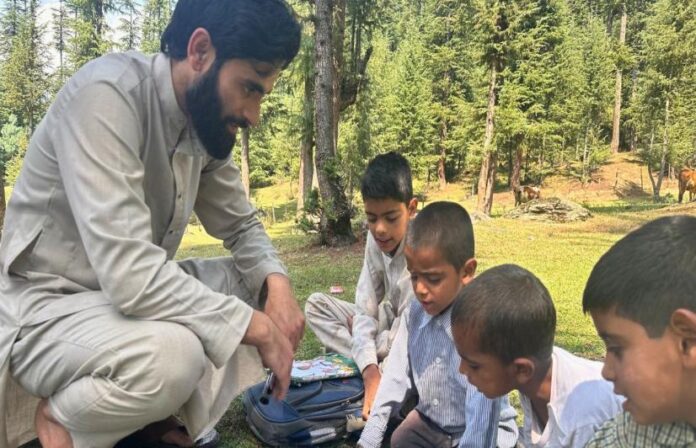

This school is no brick-and-mortar institution where children sit on benches in well-equipped classrooms. It is in the lap of nature, among the towering pine trees, with little to no infrastructure.

There is a whiteboard that Bilal Ahmad Kumar (27), the teacher, uses to introduce his students to their subjects of study, besides picture books from which children read. Sitting on the grass patch, children learn Mathematics, Enghubalish, Science, Kashmiri, and much more.

Kumar runs the seasonal school from March to September as the semi-nomadic communities of Gujjars and Bakarwals move from the Jammu region to Kashmir during this period, in search of better pastures for their animals. Like several others, Yousuf’s family lives in a makeshift kotha (mud hut) and sells cattle, ghee, and milk to make a living in Chindermarg. As the winter approaches in September, they return to Rajouri, their hometown located in the Jammu division.

Gujjars and Bakarwals constitute nearly 12% of the population of Jammu and Kashmir. Together, they form the third-largest ethnic community in the Union Territory. However, education had been a distant dream for them until the Jammu and Kashmir government set up seasonal education centres under Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan in 2003.

To run the school, the Union Ministry of Education sanctions Rs 6,000 per migratory child and provides Rs 2,500 per seasonal centre for the purchase of teaching and learning equipment, including a whiteboard, easel, markers, dusters, and interactive charts. As these schools function in open meadows, they do not even have a toilet. The only other facility that the government has provided here is a tent, which is installed as and when required.

“According to our education department, more than 33,000 children study in seasonal schools. Every year, nearly 1,500 teachers are hired for a six-month period to instruct them,” Rajeev Rai Bhatnagar, adviser to the Lieutenant Governor of Jammu and Kashmir, told 101Reporters.

“These schools hold a high priority for the government as the children from nomadic communities have limited educational opportunities. So, the government is committed to ensuring all necessary facilities for their benefit. In 2021, the Union Territory administration raised the salaries of seasonal teachers from Rs 4,000 to Rs 10,000 per month,” Bhatnagar stated.

High-risk, low rewards

Despite their dedication, volunteer teachers do not get major benefits. They are temporary workers who are paid Rs 10,000 per month, which means Rs 60,000 for six months. Like other seasonal teachers, Kumar wants the government to provide him with a full-time job in the same field.

Kumar has been running the seasonal school for the last three years. “When families migrate after six months, we are left unemployed for the rest of the year. We do not get any money from the government when the school remains closed. So, we have no option but to work as labourers then,” he told 101Reporters.

While he applauded the government’s initiative for the children’s betterment, he wished that the volunteers be given some additional benefits — a salary hike and full-time jobs — considering the risks they take to impart education.

Kumar resides at Chittergul, located 15 km from Chindermarg. Six days a week, he navigates through the deep forest, with no roads or connectivity, to reach the seasonal school. In recent years, bear attacks have been on the rise here, resulting in fatalities and severe injuries.

Seasonal teachers try to get back home before sunset, but sometimes, they are stranded due to inclement weather. In such circumstances, the families of their students arrange a separate hut and food for them. Most often, the community head makes these arrangements. However, other families volunteer to help if the stay exceeds a few days.

Yousuf noted that several of these seasonal teachers choose to stay with families like his throughout the educational season as reaching far-flung and secluded areas daily is a daunting task.

“Earlier, students from semi-nomadic communities had to abandon their education due to their yearly migration. Now, I trek to this high-altitude location to teach 35 students. However, as their migration season starts, we are left with only 15 students by September-end, and our yearly contract comes to an end,” Kumar said. Though the Chindermarg seasonal school has only one teacher, there are many seasonal educators in the Chittergul area.

Two schools of life

The students from semi-nomadic communities are learning from two types of schools now — traditional and formal. Living in the highlands with their sheep and goats, the mornings of Irshad and Iqbal, Class II students of the seasonal school in Chindermarg, look very different from that of the children in cities. Before picking up their bags and leaving for the school located a few steps from their huts around 10 am, they assist their elders in herding cattle to the meadows.

“I wish to be a teacher,” Irshad says confidently. He is inspired by and is in awe of Kumar and wants to teach the children from his community when he grows up.

Iqbal aspires to be a doctor who will provide the much-needed medical care to his community’s sick people, who struggle to access healthcare services. “We love to study here. It is tough for us due to the annual migration, but these teachers visit us every day and help us learn so many new things,” he says with gratitude. Most of the children in Chindermarg complained of not having many friends as they are constantly changing schools.

After finishing school at 4 pm, Irshad and Iqbal will return to cattle rearing, where they watch over the animals and fetch water from nearby ponds and lakes for them and for personal use. Unlike regular primary school students, they do not get mid-day meals at school.

In the next six months, Irshad and Iqbal will continue their studies in Rajouri, before coming back with renewed zeal to get admission in Class III.

“Had it not been for the teacher here, our children would have been deprived of learning opportunities. This teacher is helping our children have bigger dreams,” sums up Yousuf, with a smiling face and twinkling eyes.

(Sadaf Shabir and Fahim Mattoo are Kashmir-based freelance journalists. This article has been published courtesy of

an arrangement with 101Reporters, a pan-India network of grassroots reporters.)